Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera: Life and Work

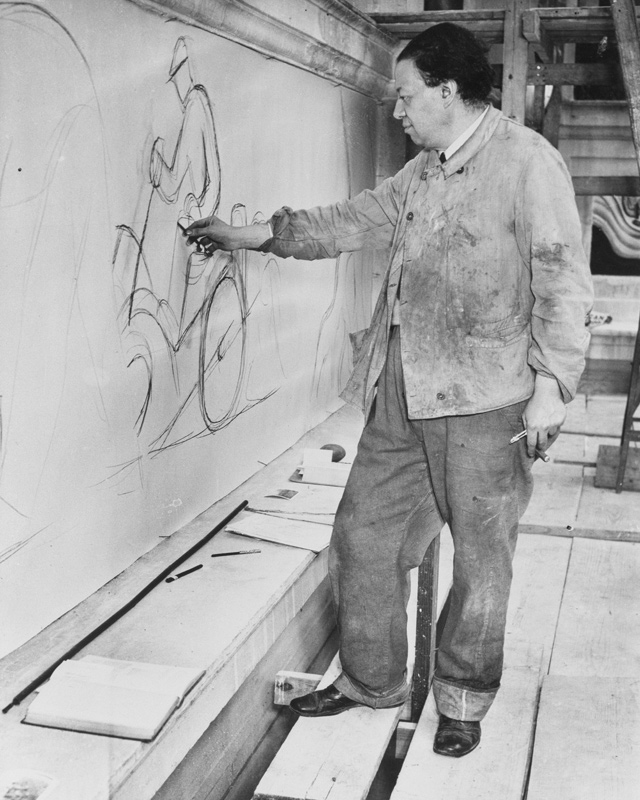

Diego Rivera working Detroit industry murals

Diego Rivera working Detroit industry muralsDiego Rivera stands as one of the most influential and controversial artists of the 20th century, whose monumental murals transformed public spaces into canvases for social commentary and cultural celebration.

Born in revolutionary Mexico and shaped by European artistic traditions, Rivera became the leading voice of Mexican Muralism, creating works that bridged the gap between high art and popular culture.

His life was as dramatic and complex as his art, marked by passionate relationships, political activism, and an unwavering commitment to depicting the struggles and triumphs of the Mexican people.

Biographical Data

Diego María de la Concepción Juan Nepomuceno Estanislao de la Rivera y Barrientos Acosta y Rodríguez was born on December 8, 1886, in Guanajuato, Mexico, to Diego Rivera Sr., a municipal councilor and editor, and María del Pilar Barrientos. Tragically, his twin brother Carlos died at the age of two, leaving Diego as the surviving child in a family that would later welcome his sister María del Pilar.

From an early age, Rivera displayed an exceptional talent for drawing, covering the walls of his family home with sketches that ranged from trains to human figures. Recognizing his artistic gifts, his parents enrolled him in evening art classes at the age of ten. His father, despite initial reservations about art as a career, eventually supported his son's artistic ambitions.

Rivera's childhood was marked by the political turbulence of Mexico during the late 19th century. The country was undergoing significant social and economic changes under the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, experiences that would later profoundly influence his artistic vision and political consciousness. His family's middle-class status provided him with educational opportunities that many of his contemporaries lacked, setting the stage for his future artistic development.

In 1896, at the age of ten, Rivera began his formal artistic education at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City, one of the oldest and most prestigious art schools in the Americas. Here, he received traditional European-style training in drawing, painting, and sculpture, studying under teachers who emphasized classical techniques and academic standards. This rigorous foundation would prove invaluable throughout his career, even as he later rebelled against many of its conservative principles.

Apprentice Years in Europe

In 1907, at the age of 21, Rivera received a scholarship from the governor of Veracruz to study art in Europe, marking the beginning of a transformative fourteen-year period that would fundamentally shape his artistic vision. He initially settled in Madrid, where he studied under Eduardo Chicharro and immersed himself in the works of Spanish masters like Velázquez, Goya, and El Greco at the Prado Museum.

Rivera's European sojourn took him through various artistic movements and geographic locations. After two years in Spain, he moved to Paris in 1909, arriving at the height of the avant-garde revolution. The City of Light was experiencing an unprecedented explosion of artistic innovation, with movements like Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism challenging traditional artistic conventions.

In Paris, Rivera encountered the works of Paul Cézanne, whose influence would prove lasting and profound. He also befriended fellow artists including Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine, and most significantly, Pablo Picasso. Rivera's work during this period shows his experimentation with various modernist styles, particularly Cubism, which he embraced enthusiastically between 1913 and 1917.

During his Cubist period, Rivera created works that demonstrated his mastery of this revolutionary style while maintaining his own distinctive voice. Paintings like "Zapatista Landscape" (1915) showed how he could incorporate Mexican themes and imagery into European modernist frameworks, foreshadowing his later synthesis of international artistic techniques with Mexican subject matter.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 disrupted the Parisian art scene, but Rivera continued his artistic development, traveling to Italy in 1920-1921 to study Renaissance frescoes. This Italian journey proved crucial, as he studied the techniques of masters like Giotto, Masaccio, and Michelangelo, learning the technical skills that would later enable him to create his monumental murals. The experience of seeing how Renaissance artists had decorated public spaces with narratives of religious and civic importance provided Rivera with a model for his own future public art projects.

Mural Painting

|

Rivera's return to Mexico in 1921 coincided with a cultural renaissance following the Mexican Revolution. The new government, led by President Álvaro Obregón and his Minister of Education José Vasconcelos, sought to create a national cultural identity that would unite the country's diverse population. Vasconcelos commissioned Rivera and other artists to create murals in public buildings, launching what would become known as the Mexican Muralism movement. Rivera's first major mural project was "Creation" (1922-1923) at the National Preparatory School in Mexico City. This work marked his transition from easel painting to monumental public art, though it still showed strong European influences in its allegorical approach and classical figures. However, Rivera quickly evolved toward a more distinctly Mexican style and subject matter. |

"On his return to Mexico, Diego Rivera was immediately enlisted by José Vasconcelos to help carry out the government's cultural policy; after ten years of civil war the minister of education was in search of a new form of artistic expression for his programme. He had begun to put interested of the country to work to use his Mexican ideology and humanist ideals in a program of wall-paintings, and was determined, through the comprehensive cultural reform movement that he proclaimed, to support the social and racial equality of the Indian population which had been the ideal of the Revolution and, after centuries of Spanish-Christian blocking of Indian cultural integration, to reclaim the independent Mexican national culture. The educational use of wall paintings was an important instrument of his policy; by this means he wished to demonstrate a break with the past, although not with tradition, and above all , to establish a rejection of the colonial epoch and nineteenth-century European culture." ~ Kettenmann, Andrea. Diego Rivera, 1866-1957. A Revolutionary Spirit in Modern Art. 2022 |

His breakthrough came with the murals at the Ministry of Public Education (1923-1928), where he created a comprehensive visual narrative of Mexican life, history, and culture. These murals covered over 1,600 square meters and included scenes of indigenous festivals, revolutionary struggles, industrial labor, and rural life. Rivera developed his signature style during this project: bold, simplified forms; earth-toned color palettes; and compositions that could be read and understood by viewers regardless of their educational background.

The technical aspects of Rivera's mural painting were as impressive as their artistic and social impact. He mastered the ancient technique of fresco, painting on wet lime plaster so that the pigments would become permanently integrated into the wall surface. This technique required rapid, confident execution and extensive planning, as mistakes could not easily be corrected. Rivera's ability to work on such a large scale while maintaining artistic quality and narrative coherence demonstrated his exceptional skill and vision.

Rivera's murals at the National Palace in Mexico City, begun in 1929 and continued intermittently until his death, represent perhaps his greatest achievement. The central mural, "The History of Mexico," presents a sweeping panorama of Mexican civilization from pre-Columbian times through the revolution and into an imagined socialist future. These works demonstrate Rivera's ability to synthesize complex historical narratives into visually compelling and accessible art.

Communist Ideology for Capitalist Clients

One of the most fascinating and controversial aspects of Rivera's career was his ability to secure major commissions from wealthy capitalist patrons while maintaining his communist beliefs and creating art that often criticized the very system that funded it. This apparent contradiction created numerous conflicts and scandals throughout his career but also enabled him to reach audiences far beyond the traditional art world.

Rivera joined the Mexican Communist Party in 1922 and remained committed to Marxist ideology throughout his life, though his relationship with the party was often turbulent. His communist beliefs were not merely intellectual positions but deeply held convictions that shaped his artistic vision and choice of subjects. He saw art as a weapon in the class struggle and believed that artists had a responsibility to serve the people rather than elite patrons.

Despite these beliefs, Rivera accepted commissions from some of the wealthiest individuals and institutions in the United States during the 1930s. His murals at the San Francisco Stock Exchange (1930-1931) and the Detroit Institute of Arts (1932-1933) were funded by capitalist institutions, yet they contained subtle and sometimes not-so-subtle critiques of capitalism and celebrations of workers and industrial production.

Rivera Court at the Detroit Institute of Arts

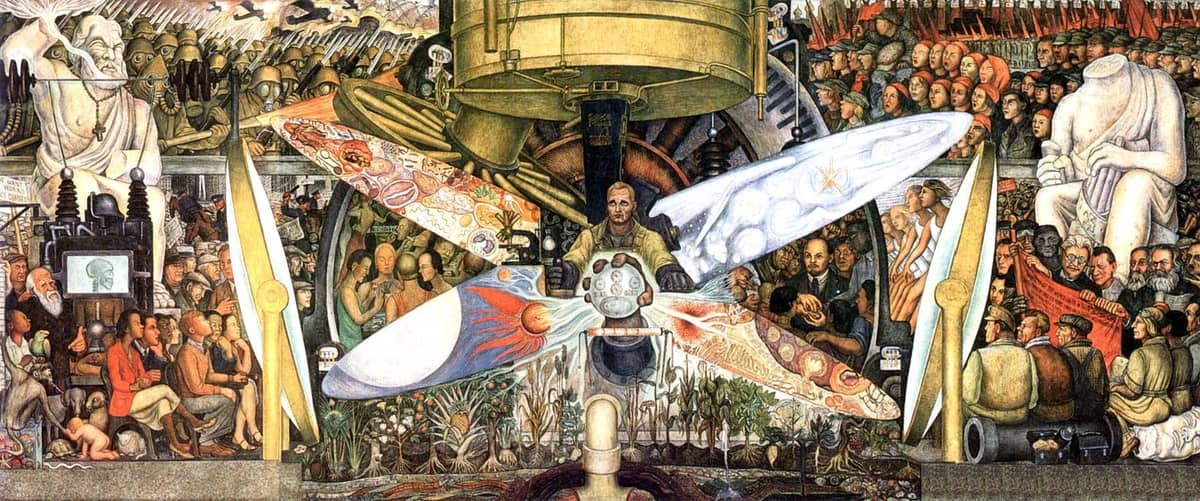

Rivera Court at the Detroit Institute of Arts Rivera - Man at the Crossroads

Rivera - Man at the CrossroadsThe most famous controversy occurred with his commission for Rockefeller Center in New York City in 1933. The mural, titled "Man at the Crossroads," was intended to celebrate human progress and technological advancement. However, Rivera included a prominent portrait of Vladimir Lenin and other communist imagery that outraged his patrons. When Rivera refused to remove Lenin's image, the Rockefellers had the mural destroyed, creating an international scandal that brought Rivera unprecedented publicity.

This incident exemplified the tensions inherent in Rivera's position as a communist artist working for capitalist patrons. He justified these arrangements by arguing that he was using capitalist money to create art that would ultimately serve revolutionary purposes. His patrons, meanwhile, were often drawn to his artistic skill and international reputation while hoping to minimize or ignore the political content of his work.

Rivera's ability to navigate these contradictions demonstrated both his pragmatism and his commitment to reaching the broadest possible audience with his art. He understood that working within the capitalist system, while compromising in some ways, allowed him to create public art on a scale that would have been impossible through other means.

From Recognition to Renown

By the 1930s, Rivera had achieved international recognition as one of the world's leading artists. His murals had been featured in major museums and public buildings across Mexico and the United States, and his work was being collected by major museums worldwide. This period saw Rivera's transformation from a respected artist to a global celebrity whose personal life attracted as much attention as his art.

Diego y Frida, husband and wife

Diego y Frida, husband and wifeRivera's marriage to fellow artist Frida Kahlo in 1929 contributed significantly to his public profile. Their relationship, marked by mutual artistic respect, political collaboration, and personal turbulence, became one of the most famous artist couples in history.

Both artists were committed communists and Mexican nationalists, and their home became a gathering place for intellectuals, artists, and political figures from around the world.

During this period, Rivera's artistic output remained prodigious. In addition to his major mural projects, he continued to paint easel works, create illustrations, and write about art and politics. His portable works from this period show the same commitment to Mexican themes and social commentary as his murals, but in more intimate formats that allowed for different kinds of artistic exploration.

Rivera's international exhibitions during the 1930s and 1940s cemented his reputation as a major figure in 20th-century art. Major retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and other prestigious institutions brought his work to new audiences and established him as a key figure in the development of modern art. These exhibitions also helped to introduce Mexican art more broadly to international audiences, contributing to a greater appreciation for Latin American cultural production.

The artist's political activities during this period also contributed to his renown, though sometimes controversially. His involvement with Leon Trotsky, who lived in Rivera and Kahlo's home during his Mexican exile, created tensions within the communist movement and led to Rivera's expulsion from the Mexican Communist Party in 1929. His later reconciliation with the party in 1954 demonstrated the complex evolution of his political thinking.

Dream of Peace and Unity: The Last Journey

Rivera's final years were marked by both declining health and a renewed sense of purpose in his art. Despite suffering from cancer and other ailments, he continued to work on major projects that reflected his lifelong commitment to social justice and his evolving vision of Mexico's place in the world.

Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park)

Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park)One of his most ambitious late projects was the mural "Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park" (1947-1948) at the Hotel del Prado in Mexico City. This work synthesized many of the themes that had occupied Rivera throughout his career, presenting a panoramic view of Mexican history through the lens of a dream sequence. The mural featured historical figures from different eras mingling in Mexico City's central park, creating a timeless vision of Mexican identity and continuity.

The work initially caused controversy because it included the phrase "God does not exist" in a banner held by 19th-century liberal reformer Ignacio Ramírez. After protests from Catholic groups, Rivera agreed to remove the offending phrase, demonstrating a pragmatism that had characterized his career-long negotiations between artistic vision and public acceptance.

Rivera's final major project was a mural at the Hospital de la Raza (1953-1954), which depicted the history of medicine in Mexico from pre-Columbian times to the modern era. This work reflected his continued interest in synthesizing Mexican indigenous traditions with modern scientific knowledge, themes that had appeared throughout his career but took on new urgency as he contemplated his own mortality.

In his last years, Rivera also worked on a project that would have been his most ambitious: a series of murals for the National Palace that would have covered the entire building and presented a complete visual history of Mexico. Though he was unable to complete this project before his death, the existing murals represent one of the most comprehensive artistic treatments of national history ever attempted.

Rivera died on November 24, 1957, at the age of 70, leaving behind a legacy that extended far beyond his artistic achievements. His funeral became a national event, with thousands of mourners paying their respects to an artist who had helped define Mexican cultural identity in the 20th century.

Diego Rivera's life and work represent a unique synthesis of artistic excellence, political commitment, and cultural nationalism. His ability to create art that was simultaneously sophisticated and accessible, local and universal, revolutionary and beautiful, established him as one of the most important artists of his era. His influence continues to be felt today, not only in Mexico but throughout the world, wherever artists seek to create public art that speaks to social justice, cultural identity, and human dignity. His dream of peace and unity, expressed through decades of monumental art, remains a powerful vision for the role that art can play in creating a more just and equitable world.

Okay, so now I've put on some ads from Amazon - from which I may earn a few cents. (2025)